The true utility of Euler's work was not evident until the mid to late 1800's. At this time George Westinghouse, Charles Steinmetz, and others needed a way to conveniently calculate quantities associated with the newly invented AC power. Previously, people had only used DC power, and found attempts to implement AC to have unpredictable and often deadly results. Indeed, Thomas Edison, the famous inventor of the light bulb, called AC power the work of the devil, deeming it useful only for killing people.

Today, by using complex numbers, electrical engineers and physicists can easily calculate the behavior of electrical oscillation, AC power, and communication signals and circuits. A major fraction of modern technology, that which uses waves and oscillations, is made possible by Euler's invention.

To understand the utility of Euler's complex numbers for waves and oscillations, let's consider a typical "sine" or "cosine" wave. This may be the mathematical representation of an oscillation, a vibration, a resonance, or a wave. Typical applications include acoustical waves, AC power systems, laser and fiber optics communication systems, radio and television components, and cell phones. Below are shown some oscillations that can be mathematically described by cosine waves.

Notice the pointer swings wildly back and forth from positive voltage to negative voltage and back again in cycles. This is because our society uses "AC power" where AC stands for "alternating current". Use of AC power allows us to use transformers to jack up the voltage to levels of hundreds of kilovolts for efficient delivery of power from power plants hundreds of miles away, and to return it again to relatively safe levels for use in the household. Transformers do not work with simple, steady, "DC" power. Without use of AC power and transformers, power plants would have to be distributed though out large cities and the use of distant power sources such as from dams, water falls, or wind turbines would be impractical, because most of their energy would be lost in bringing the power to the cities.

For the purpose of animation, the rate of oscillation has been slowed way down. Real AC power reverses direction 120 times a second, too fast for the human eye to follow, and requires a special "AC" setting on a voltmeter. AC meters read an "RMS" voltage which is similar to the "amplitude" that we will discuss below.

Development of AC power required the simultaneous development of the mathematical method that we will be describing in this lesson. Because of its complexity (which was eventually overcome by these mathematical methods) Thomas Edison never did accept accept AC power and considered it the work of the devil.

Electronic audio signals, such as those going through your stereo, walkman, iPod, and cell phone oscillate in much the same way, although their rate of oscillation is much greater and various with the pitch of the sound being generated. They reverse direction 500 to 10,000 times per second. TV,radio, and cell phone transmission signal also oscillate in a similar fashion, at a rate of 1 million to 5 billion times per second. Laser signals (such as those that carry most of the internet traffic in optical fibers) reverse at a rate of several trillion (2 to 6 × 10 12) times per second. All these types of signals can can be analyzed by these methods.

Usually such a wave, or oscillating voltage fluctuates up and down in a very regular pattern, just the same way as the cosine function does, except here the function is plotted versus time instead of angle.. Electrical engineers and physicists use a measuring device called an oscilloscope to make graphs of rapidly oscillating waveforms. Oscilloscopes are amazingly fast and can make graphs of oscillations that reverse up to several billion times per second, as well as those slower than that.

The mathematical formula for such oscillation is (written for the voltage for the sake of definiteness):

where A is the "amplitude" (how tall the oscillations are), ω is the "angular frequency" (a measure of how fast the voltage oscillates), and ϕ is the "phase shift" (a measure of how much the peaks are shift over from the starting y-axis. You can alternately use sine functions to express the same wave, or a mix of sines and cosines. We should point out that the argument of the cosine function, the ωt + ϕ in the above equation, is in the angular units of radians as discussed in the first animation. For a fairly detailed discussion of phase click here.

We can use this mathematical representation for all sorts of waves, oscillations, vibrations, and resonances. We sometimes call this (and the yet discussed complex equation for waves) a "wavefunction". Technically, true waves, as opposed to oscillations and vibrations, require a slight modification of the above equation, but we won't get into that now.

The problem comes when you want to add two waves together, or calculate the effect on the wave of passing through a particular wire or component. These types of mathematical manipulations are typical of what is needed in calculation to design wave related technology, such as AC power components or systems. Doing the necessary calculations with sines and cosines is quite tedious. We shall next demonstrate this to make our point.

To understand the problem involved, consider the two waves shown below

.

.

The sum of the red and blue wavefunctions added together is the green wavefunction shown at the right. It is not very obvious to the average person that this is indeed the sum.

Unless you do this a lot, it is difficult to simply glance at two wavefunctions and know what their sum will be. Wavefunctions, when added together can do strange things. They can "constructively interfere", "destructively interfere", or do a combination to the two.

Unless you do this a lot, it is difficult to simply glance at two wavefunctions and know what their sum will be. Wavefunctions, when added together can do strange things. They can "constructively interfere", "destructively interfere", or do a combination to the two.

Ok, so it is complicated, but how do we sum the two waves mathematically?

Summing two waves using trigonometric functions.

Mathematically we can expression their addition as:

.

.

Experimentally, we know that the sum of two waves of equal frequency always results in a third wave of the same frequency, which we can generally express as:

Now the puzzle is: how to solve for the resulting amplitude, A3, and phase, ϕ3 ,in terms of the known quantities A1, ϕ1, A2, and ϕ2.

This can be a very difficult problem, but I will lead through by perhaps the fastest way (fastest without use of complex numbers). There are many slower methods and ways to get hopelessly lost.

We start by applying the trigonometric relationship:

This relationship is not something the average person would be expected to know, however the ancient Greeks (Ptolemy) did discover it. Applying this relationship to the two above formulas for v3(t), we get:

The first equation can be factored as:

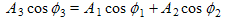

The time dependent parts of the equations are the cos ωt and sin ωt factors. In order for the upper equation to equal the lower one at all times, the coefficient (or multiplier) of the cos ωt in the first equation must equal the cos ωt coefficient in the second equation. Likewise for the sin ωt factors. Thus, we have the two equations:

We need to solve these two equations for the two unknowns A3 and ϕ3 . We can eliminate ϕ3 and solve for A3 by squaring both equations and then adding them, remembering that sin2ϕ + cos2ϕ = 1. This gives us:

.

.

Taking the square root yields:

Similarly, we can eliminate A3 from the two equations and solve for ϕ3 by dividing one equation by the other:

Phew! That was a lot of work! At this point, you should understand the need for a faster method of adding wavefunctions together. While the above solution is correct, it is neither fast nor transparent. For something as important as the technology of waves, we need a faster, more transparent method to add two waves. This better method will be with "the complex representation". Before we get into that, we shall discuss an intermediate representation that takes us half way there.

Phew! That was a lot of work! At this point, you should understand the need for a faster method of adding wavefunctions together. While the above solution is correct, it is neither fast nor transparent. For something as important as the technology of waves, we need a faster, more transparent method to add two waves. This better method will be with "the complex representation". Before we get into that, we shall discuss an intermediate representation that takes us half way there.

© P. Ceperley 2007

| Good references on WAVES | Good general references on resonators, waves, and fields |

|---|---|

|