| All postings by author |

| previous: 1. Introduction |

| up: Contents |

| next: 2.2 Complex math derivation |

Simple Resonators - Shock excitation

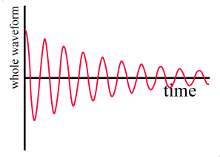

2.1 The decay equationOne way to excite a resonance is with a shock, such as the striking of a bell, hitting a tuning fork, plucking a violin string or the exciting of any resonator with a suitable impulse. The resonator then oscillates in a decaying fashion as shown in the animation below. Click on it to start it.

| Figure 1. The bell ringer. Click on the figure to start or restart it. Mousing off will stop it (the sound requires a restart click to restart it). Real bells oscillate much, much faster than is indicated here and usually resonate at more than one frequency. |

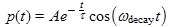

The equation for this decaying oscillation is:

This is the decay equation. The decay equation is the topic of this posting.

The decay equation is written, in this case, in terms of the acoustic pressure p(t), the small oscillating pressure that our ears tell us is sound. The quantity τ is the time constant of the decay and A is the amplitude at the starting time, i.e. at t = 0 where t is time. Mathematically, e raised to the time dependent power −t/τ is responsible for the decaying amplitude while the cos(ωt) mathematically causes the oscillations. The mathematical constant e (equals 2.718... ) is the base of the natural logarithm.

You can further understand the two parts (factors) of Equation (1) as follows:

| Table 1. Parts of Equation (1) | About exponential functions | |

|---|---|---|

(1a)

(1a)

|

The first factor, the decaying amplitude, is an exponential function. It also serves as an envelope for the second term. In electronics, an envelope is a curve that bounds another curve. The envelope can be seen in the above animation by clicking on "show envelope". It is also shown in Figure 2b below. |

Figure 2b below shows an exponential function such as Equation (1a). Such a function is characterized by a time constant. The time constant, τ, is the time the function requires to fall to 1/e (i.e. 0.37 or 37%) of its its initial value, as is shown in Figure 2b with the blue dots. One amazing thing about this function is that you can use any point along the curve as the "initial" point, and one time period later the function will equal 37% of this "initial" value. That is to say, it is a constant of the function, just like the slope of a straight line is the same no matter where it is measured.

Another interesting feature of this function is that it becomes a straight line if the scale on the vertical axis is logarithmic, as is shown in Figure 2d. Investors often use this type of graph for plotting the value of various investments. An investment that is rising (or falling) at a constant percent rate of return will be exponential and therefore straight on this type of graph. It is also true that the slope of the straight line will be proportional to the rate of return, making of this type of graph good for quick identification of the rate of return of investments. Some fields of study use half-life t½ to characterize exponential decay in place of the time constant. This is the time this function takes to fall to half its "initial" value. The half-life and time constant are related as t½ = τ ln(2) = τ×0.693 . Exponential functions are the solution to a simple first order differential equation and define the behavior of many scientific phenomena. See these sites for discussions of exponential growth and exponential decay. |

| cos(ωdecayt) (1b) | The second factor is the constant oscillating sinusoid. A sinusoid is any sine or cosine function or sum of the two that have the same frequency, ω. A typical sinusoid is shown in Figure 2c. | |

Exponential decay is the best known type of decay for simple resonators; however, some resonators decay differently. For example, if sliding friction dominates in a resonator (such as between two rubbing parts), then the decay (i.e. the envelope) may be linear, allowing the resonator to totally stop in a finite time, instead of just asymptotically approaching zero, as in Figures 1 and 2a. Other types of decay would be governed by different differential equations, primarily different in the term that involves the source of the decay. We will continue to focus on exponential decay in this posting.

LRC circuit resonators

We next explore a second resonator to complement the example of the bell above. This second resonator is the LRC* circuit resonator. The LRC circuit is a typical linear resonator which was presented in the last posting. We will use this circuit to derive the basic decay equation presented above (Equation (1) ). We picked the LRC ciruit because of its widespread use in all sorts of electronics, because it is simple, and it is often presented in text books as being representative of all simple resonators. It sees use in filters, matching circuits, and oscillators in many types of electronic devices. The resonant frequencies of LRC circuits can range from tens of Hertz (for very low audio signals) to GHz for computers, cell phones, and GPS devices. See my posting on Marconi and the spark gap transmitter as an example of an historic use of an LRC resonator.

*Standard text books vary on the naming of this circuit. LRC, RLC, and LCR are used.

An LRC circuit is shown in the photograph at the right in Figure 3 and consists of an inductor, a resistor, and a capacitor in series. The inductor is basically a small coil that provides a "momentum" to the current flow. The capacitor has two plates separated by an insulator (non-conductor) and stores electrical charge, similar to the Leyden jars that Benjamin Franklin used. The resistor is a circuit element that provides some electrical resistance to current flow and in the case of an LRC resonator, it provides damping to the oscillations.

The animation below shows a typical test setup used to excite and observe the decaying oscillations of this resonator. On the left of this figure, we see a pulse generator used to shock-excite the resonator (in the middle). On the right is an oscilloscope used to observe the oscillations in the resonator. Click on the figure to start the animation and mouse off to stop it. Note that in student electronics labs, a general purpose signal generator, set to make square waves, often replaces the pulse generator, with the resulting signal being slightly more complicated but still generally similar to the result shown here. The oscillations are usually too fast for the eye to follow, but the oscilloscope captures them for viewing.

| Figure 4. Test setup for monitoring the resonance of an LRC circuit using shock excitation and decay. After the pulse, the pulse generator acts as a simple wire connecting points 1 and 2. This animation shows symbols in place of the actual inductor, resistor, and capacitor, shown in Figure 3. The pulsating shading inside the inductor and capacitor is meant to illustrate the invisible oscillating magnetic and electrical energies in these components. |

|

Mathematical derivation of the decay equation

In this section we will show a derivation of the decay equation, Equation (1).

For this derivation, we will use the LRC series circuit as our example elemental resonator. As was discussed in the last posting, all the elemental resonators have equivalent defining differential equations and will behave in a similar fashion.

This circuit is shown at the right and is made up of an inductor L, a resistor R, and a capacitor C in series as shown in Figures 3 and 4 above. The same oscillating current I(t) flows through all three elements, while the voltages across the three elements differ from each other. The oscillating charge q(t) is the charge on the upper plate of the capacitor C (the lower plate has an equal magnitude but oppositely signed charge).

| Table 3. Combine the above in the following steps: | |

|---|---|

(3a)

(3a)

| Substituting Equation (2e) into the Equation (2d), we get the defining differential equation for the behavior of this circuit. This is the differential equation we listed in Figure 1 of Section 1 for the LRC circuit, but here we have actually derived it! |

| Equation (3a) is a very standard second order differential equation with known solutions of the form of Equation (1). In Equation (3b), p in Equation (1) has been replaced with q which is the oscillating variable in Equation (3a). To be completely correct, the cosine factor could have an arbitrary phase associated with it, i.e. cos(ωdecayt) ⇒ cos(ωdecay + φ) , where φ is the phase shift. At the same time, φ is not needed in the case at hand (it equals zero) so we leave it out for simplicity. | |

| Equation (3b) is our decay equation! We are finished! We have derived the decay equation! | |

Derivation of constants for Equation (3b)

We will next derive equations for the constants τ and ωdecay in Equation (3b) above. This effort will prove to be more work than deriving Equation (3b).

| Table 5. Now we're ready for some results (in our pursuit of the constants)! | |

|---|---|

(5a)

(5a)

| Let's look at Equation (4c). As time progresses, the sine and cosine terms rise and fall out of phase with each other. In order for Equation (4c) to be valid for all times (i.e. the left side equaling zero at all times), both the sine and cosine coefficients need to be zero. Setting C=0 in Equation (4e) and solving for τ gives an equation for the time constant, τ (with units of seconds). |

(5b)

(5b)

| Setting B=0 in Equation (4d), solving for ωdecay, and using Equation (5a), gives an equation for the shock-excited angular resonant frequency (or decay angular resonant frequency). ω0 is defined in the next equation. |

(5c)

(5c)

| ω0 is the angular resonant frequency for continuous excitation (discussed in a future posting) as opposed to shock excitation being discussed here. The effect of the decaying amplitude is to slightly reduce the effective frequency of the oscillations. (Perhaps this is easiest to understand in a mechanical resonator like the pendulum: drag will slow down the bob on its swings.) The units for both ωdecay and ω0 are radians per second. |

(5d)

(5d)

| In the case of small damping, i.e. when τ>>LC, then ωdecay approximately equals ω0 and the distinction between ωdecay and ω0 goes away. |

(5e)

(5e)

|

The decay resonant frequency in Hz (or cycles per second) equals ωdecay divided by  . You can treat this as a simple unit conversion if you wish: . You can treat this as a simple unit conversion if you wish:

|

(5f)

(5f)

|

In doing the experiment shown in Figure 4, we usually observe the voltage across the capacitor on the oscilloscope screen and not the charge. We use Equation (2a) above to convert our q(t) from Equation (3b) into VC(t), where τ and ωdecay are given by Equations (5a) and (5b).

If we should instead wish to know the voltage across the resistor or inductor, then we could similarly have used Equations (2b), (2c), and (2e) to convert our q(t) into these quantities as a function of time. Be warned however, the algebra for VR(t) and VL(t) is more involved than that shown here for VC(t). It might be easier to use complex methods to determine these voltages as discussed in the next posting. We would expect to get a phase shift φ as mentioned to the right of Equation (3b). All the quantities, q(t), VC(t), VR(t), and VL(t), behave in very similar fashions: all are sinusoidal oscillations with exponential decaying amplitudes and look like the function in Figure 2a. All have the same values for τ and ωdecay. |

| Table 6. General results for all simple resonators | |

|---|---|

(6a)

(6a)

| The various simple resonators shown in the previous posting were all governed by differential equations similar to that of the LRC circuit shown in Equation (6a). In the rest of this table we show the results when the derivation is done in terms of these general coefficients instead of those specific for the LRC circuit. This gives us results that are applicable to this whole class of resonators. I should point out that in this table C is not the capacitance, but instead it is the constant in the last term in Equation (6a). |

| Predictably, all these simple resonators respond to shock excitation in very similar ways: | |

(6b)

(6b)

|

All respond with a decaying sinusoidal oscillation of the form of Equation (6b), where q(t) could be replaced by any of the equivalent oscillating displacement parameters of a simple resonator, shown in Figure 2 of the last section. A1 is the amplitude of the parameter at t=0.

Because the kinetic and potential parameters of Figure 2 of the previous section are proportional to the derivatives of the displacement parameters they will also be of the same form as Equation (6b) with perhaps a phase shift φ in the cosine factor as noted with regard to Equation (3b) above. The proportionality is easier to understand in the complex notation of the next posting, Equations (6e) and (6f) ) |

| τ = 2A/B (6c) | All have decay time constants τ given by (6c) |

(6d)

(6d)

| All have decay angular resonant frequencies given by (6d), |

(6e)

(6e)

| Equation (6e) defines the ω0 in Equation (6d). Again, in this equation, C is not the capacitance, but just the constant of the last term of the general differential equation (6a). |

| P. Ceperley, Jan. 2010. |

|

(4a)

(4a)

(4b)

(4b)