| All postings by author | previous: 2.1 Shock excitation | up: Simple resonators - Contents | next: 2.3 Strong damping - critical damping |

Simple Resonators - Shock excitation

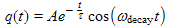

2.2 Complex math derivationThe above animation shows decaying oscillations of a bobble head. It also shows the graphical form of the associated complex phasor* (the red rotating arrow) which we use (in its mathematical form) in the next table. As you see in the animation, the phasor decays along with the amplitude of oscillations of the bobble head. Click on the animation to start it. The hand from above provides the "shock" to start the oscillations.

*The mathematical form of the complex phasor (used in Equation (6c) below for example) is the complex expression Ae−t/τeiωdecayt. As a function of time, this function traces out a circular path on the complex plane, traced by the red arrow tip in the animation above. The real quantity, the oscillating bobble head's location, is the projection of this arrow tip onto the real axis (i.e. the real part of the complex phasor). For more on use of complex phasors see the posting here and also the other postings in that chain of postings (index). Use of complex phasors allows us to get to the results much faster than use of real sines and cosines.

In the following table, we repeat the derivation in Tables 3, 4, and 5 of the previous posting using complex notation. This derivation is directed towards the oscillations of charge in an LRC circuit resonator, discussed in that posting.

| Table 6. Repeating the work from Tables 3, 4, and 5 above using complex math. | |

|---|---|

(6a)

(6a)

(6b)

(6b)

| Repeating the defining differential Equation (3a) for an LRC circuit and the known standard solution (3b) from above as a starting point. |

(6c)

(6c)

where s = −(1/τ)+iωdecay. (6d) |

Here we convert Equation (6b) into complex notation. In this step we replace the real sinusoid (the cos(ωdecayt) in this case) with a complex rotor (eiωdecayt in this case) and we need to remember that

the actual charge, q(t), will be the real part of the phasor, i.e. in this case the real part of Ae−t/τeiωdecayt.

This exponential form allows us to collect all of the time varying parts into one exponent with the simple complex constant s multiplying time, i.e. t. |

| dq/dt = sest (6e) | The first derivative of q(t). Note that in complex notation (as we have here), the derivative of q(t) is proportional to q(t). Note that the first factor on the right side of the equation, i.e. the s is complex and will represent a phase shift and well as an amplitude multiplying factor, i.e. s = |s|eiφ . For an animation showing a phasor changed in amplitude and phase via multiplication by a complex constant click here. (Scroll up in that animation to see some explanation.) |

| d2q/dt2 = s2est (6f) | The second derivative of q(t). |

| Ls2+Rs+1/C = 0 (6g) | Substituting Equations (6c), (6e) and (6f) into the Equation (6a), we get an equation with three terms. All these terms have the common factor Aest. We have divided this out to get Equation (6g). This step and the previous two steps are much, much easier and faster using complex notation. |

(6h)

(6h)

|

We now use the quadratic equation to solve for s and get Equation (6h). We have dropped the − sign of the ± that is normally in the quadratic formula, because we are not interested in negative frequencies (which incidently, are occasionally used, for example in complex Fourier series work).

We also played with* the square root to make it imaginary so that there will be a non-zero imaginary component to s. This way &omegadecay , which equals the imaginary component of s, will not be zero. This action assures that oscillations do occur as long as 1/LC is larger than R/2L. More on this just below. *Multiplied by i (which equals the square root of −1) outside the square root and by −1 inside the square root. |

(6i)

(6i) (6j)

(6j) |

In order for the complex Equation (6h) to be true, the real part on the left side of the equation must be equal to the real part on the right side. The same is true for the imaginary parts of both sides of Equation (6h).

Equating the real parts of Equation (6h) on both sides yields Equation (6i). Doing the same with the imaginary parts gives equation (6j).

In the next part of this posting, we will see that ω0 is the resonant frequency for continuous excitation, i.e. the center of the resonance curve. The condition that the quantity inside the square root sign be positive (i.e. τ > 1/ω0) means that the decay time constant is longer than one radian of cycle time or longer than approximately one sixth of a oscillation period. Another way to say this is that the damping is not so strong that all oscillations are suppressed (which would be considered "overdamped"). With such strong damping, the LRC circuit would cease to behave as a resonator. We cover underdamping, critical damping, and overdamping in the next posting. |

| All postings by author | previous: 2.1 Shock excitation | up: Contents - simple resonators | next: 2.3 Strong damping - critical damping |