|

| Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1717-1783). |

So far we have discussed oscillations. Examples of these are oscillating voltages in AC power or in many electronic signals. They may be pressure oscillations at a point due to a sound wave passing through, or electric field oscillations at a point due to an electromagnetic wave passing through. It turns out that we can do better than just expressing oscillations at a point due to a passing wave, we can actually express the whole wave mathematically.

The mathematical trick for working with waves can be attributed to Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1717-1783). He found that the general mathematical solution to the differential equation governing simple waves traveling in the x direction are functions of the form:

y(x,t) = f(x - ct)

where c is the velocity of the wave.

To understand this concept, consider the peaked exponential function shown at the right, called a gaussian or gaussian function. The equation describing it is:

Another notation for this same equation is y = exp(−x2). This is a very useful function which is perhaps best known for describing the statistical distribution of random events, but it is also useful for several purposes in oscillations and waves. This is a totally real function, and not directly related to the complex exponential that Euler invented.

We first need to understand that if we replace the x with x −2 that the function will shift over by 2 as shown in the graph at the left. The equation is now

.

This is just a prescription for shifting something along the x axis by 2. It is sort of a shifter equation.

.

This is just a prescription for shifting something along the x axis by 2. It is sort of a shifter equation.

We can make this more general and replace x with (x − x0), giving an equation looking like:

|

The animation to the right shows the effect of a variety of x0 values.

To get the peak to move with time we substitute ct in for for x0, where c is the speed of the shifting. Thus, if c were equal to 5m/s, then at 1 second, x0 = ct would equal 5m. At 2 seconds, it would equal 10m. At 3 seconds, it would equal 15m, and so on. The point is that x0 would keep on increasing and making the peak of the curve shift continuously to the right. The animation below demonstrates this continuous shifting at a variety of velocities.

|

To summarize, we have demonstrated the continuous shifting of the gaussian function by d'Alembert's method. As we have seen, d'Alembert's function shifts the gaussian curve over to the right more and more as time progresses, just like a wave does. It turns out that it works on any function, not just the gaussian. Start with any function f(x) and substitute (x − ct) in for x and you will have a function that plotted versus x, shifts over to the right as time increases. And, as we stated before, all these shifting versions of functions happen to be the solutions to the differential equation governing simple waves.

Shifting cosine functions

|

| Simple cosine function representing a typical oscillation, written as a function of x instead of time. |

Most of us think of water waves when we think of waves: those long regular humps of water moving in towards the shore. Except for their final moment of breaking at the beach, these can be pretty accurately described in terms of cosine functions, similar to the oscillations we discussed above. We repeat one of the earlier graphs to the right which shows the function

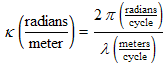

The argument of the cosine function needs to be in units of radians. On the other hand, with waves, x usually means a distance in space, in meters, for example. In order to use x here we need to first multiply it by the constant κ, the wave number, to convert the meters into radians.

The wave number is in units of radians per meter and is a measure of how tightly bunched the peaks of the wave are in the x direction. It is similar to ω, the angular frequency, which is the radians per second in an oscillation. The wave number works on x in the "spatial domain", while the angular frequency works on time, in the "time" domain.

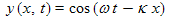

Now let's convert the static cosine function into a dynamic moving wave using d'Alembert's method, replacing the x with x−ct, i.e.

This is usually simplified by using the relation between wavenumber and angular frequency: κc = ω

Because the cosine function is symmetric around the y axis, i.e. cos(−x) = cosx, the above equation can also be written with an inverted argument

without changing its value or its graph. One of the oddities of this science is that physicists tend to use the first way of writing the equation, whereas electric engineers use the second. Mathematically they are equivalent.

Whereas in our earlier discussions on oscillations, our functions were only of one variable, namely t or time, we now have a function of two variables, x and t. It is difficult to graph the function of two variables as simply as we do a function of one variable, but we can try anyway. One way to do this is as shown to the right, to graph the function versus x for various times. If we read the graph carefully, we can see that the function is moving to the right as time progresses. That is, the waveforms for greater times are shifted to the right.

Using animation however, we can do much better and graph the function versus x as time progresses on a continuous basis. This is shown below.

|

A more general wave

To describe a real wave, we need to add a few more constants to our equation, making it look like

| An animation showing the general cosine wave as a function of x with increasing time. Mouse over the animation to see the action. Mouse off to stop it and back on to continue it. Clicking on any of the yellow buttons will restart it with a new value of the particular constant labeled on the button. The numbers over the green dots are just the results of those in the yellow buttons (see the table and associated text below for more on that.) |

The constants and variables in this equation are:

- A, the amplitude (in units of whatever the wave is related to, e.g. in a pressure wave A will have units of pressure).

It is basically the size of the wave, or more specifically the maximum height minus the average level of the wave. It is also half the vertical distance between the wave crests and the wave troughs.

- ω, the angular frequency (omega) (in radians per second.... 6.28 radians make a complete wave cycle).

How fast the wave oscillates (goes up and down) at any fixed point as the wave sweeps past you. It is another form of the frequency (see below).

- t, time (seconds).

You don't have any control over time. It just keeps going on.

- κ, the wave number (kappa) (in radians per meter.)

How tightly packed the peaks of the wave are in a snap shot of the wave (freeze it). It is inversely related to the wavelength (see below).

- x, position (in meters)

A measure of where you are along the x axis.

- φ, the phase offset (phi) (in radians).

What phase of the wave is lined up with x = 0 at zero time, (t = 0). If φ is positive, the wave initially will appear to be shifted to the left, and the reverse if φ is negative. The floating red apple (or dot) on the wave crest of the animation is at the point on the wave where the argument of the cos, all except for the φ, is zero. Just at the starting time (or time of resetting) the red dot will be at the y axis if φ = 0, to the left of the axis if φ is positive and to the right if φ is negative. If you are generally confused about phase, see the discussion at the end of this posting on phase.

- y0, the average wave height (in the same units as A).

The height offset of the wave. If the wave is centered around zero in the vertical direction, then y0 = 0. However y0 can be greater or less than zero to raise or lower the average value of the wave.

The animation to the right and above will allow you to vary these constants to better understand the effect they each have on the wave.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

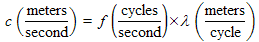

| Equations linking various parameters to each other. The frequency, f, is similar to the angular frequency, ω, except that f has units of cycles per second, instead of radians per second. One of the equations above shows how to convert one into the other. A cycle per second is officially called a Hertz, abbreviated Hz.

The wavelength, λ, is the length of one cycle (in the x direction in our examples) and has units of meters. Alternately, we can use as units meters per cycle to emphasize that is it the length of just one cycle. It is the inverse of the wavenumber times 2π as shown in the equation above. | |

Relationship between wave constants

A number of the above constants are related to each other. To the left we present a table of these relationships. You can derive these with little thought experiments, or you can consider them as sort of a units change exercise. The right hand column of the table shows this unit change logic for each equation. I've found this unit change method very convenient for quickly rederiving (or checking) the relationships when needed. You can find more on simple waves on Wikipedia.

More on phase

Phase can be a confusing topic to anyone new into the wave and oscillations field. Just what do we mean by "the phase" of a wave?

Think of the phase or phases of the moon. A short list of these are new moon, first quarter, full moon, and last quarter, all of which repeat over and over again, just like waves and oscillations do. The phase of the moon identifies what part of the lunar cycle you are considering at the moment. An oscillation or wave similarly goes through cycles. For a cosine function (oscillation or wave), the four "quarters", to use the lunar analogy, are maximum positive value (pressure, voltage, temperature, whatever the oscillation entails), zero, negative value, and zero, as shown in the graph below.

You might noticed that this graph is plotted with angle as the arguement, in degrees in our graph, however we might have used radians just as well. When we discuss phase, we always think in terms an angle: the angle which is the arguement associated with the part of the oscillation we are focused on at the moment. If we are focused on the maximum positive part of the cycle, then we say the phase there is zero degrees (look at the graph). If we are focused on the maximum negative (or minimum) part, then the phase is 180 degrees or π radians. If we are between these extremes then we can make a guess based on remembering the graph and just how far we are from the extremes. If a scientist is discussion the phase of 45 degrees (π/4 radians) then he means the wave is decreasing from the maximum and has yet to hit the first zero in its cycle.

You might also be aware that "phase" can also be used to mean slightly different, but related things and to understand the exact meaning you have to be aware of the context (just as with many, many other terms our English language). Sometimes a person will use "phase" to mean the difference in the phases of two oscillations which are going on simultaneously. The term "phase difference" or "phase shift" would be more appropriate, but that is two words instead of one. Another person might use "phase" in place of "phase offset" to mean what is the phase of the oscillation at time equals zero (and perhaps x=0 also for a true wave) as we discussed above.

© P. Ceperley, 2007.NEXT: Waves using complex phasors PREVIOUS TOPIC: The algebra of complex phasors

| Good references on WAVES | Good general references on resonators, waves, and fields |

|---|---|

|