| All postings by author | previous: 2.5 Energy in a resonator | up: Simple resonators - Contents | next: 2.7 Energy and power by complex methods |

2.6 Power loss in resonators

In the previous posting we derived approximate equations for the power loss and energy in a resonator as a function of time. The approximate formulas were:

In the previous posting we derived approximate equations for the power loss and energy in a resonator as a function of time. The approximate formulas were:

P = αU , (a) and U = U0 e−αt , (b)

We can combine these to get P = αU0 e−αt = P0 e−t/τenergy , (c)

where P0 = αU0 is the initial power loss (at t = 0 ) and τenergy = 1/α is the time constant for the decay of energy and power.

Rate of energy loss in a shock excited LRC circuit resonator

Next we calculate the power loss in an LRC circuit resonator using the formulas we derived in the last posting. This should give us a more precise formula for the power loss than Equation (c) above.

| Table 1. Derivation of -dU/dt in a shock excited LRC resonator. | |

|---|---|

(1a)

(1a)

| This is a copy of the equation we derived for the energy in a shock excited LRC resonator in the Equation (1j) in the last section. |

(1b)

(1b)

| We start the process of taking the first derivate of Equation (1a) (of U(t) ) with a minus sign . |

(1c)

(1c)

| We have combined similar terms. |

Equation (1c) is graphed below in Figure 1c. We see that the power is a pulsating decaying waveform. The frequency of pulsing is twice that of the charge oscillations of Figure 1a (you can see that both in the figure and in Equation (1c) where there is a new "2" in the arguments of the sine and cosine terms compared with Equation (1d) of the previous section for the charge oscillations.) Except for the pulsating nature, the decay of power is very similar to the decay of energy. That is, it is an exponential decay with a time constant equal to that of the energy decay (Figure 1b). The power decay time constant is equal to half of the time constant for the decay of the oscillating charge of Figure 1a.

We also see the average power loss in Figure 1c, graphed versus time. This average power is given by first factor in Equation (1c), i.e. as

Paverage = A2/Cτ exp(−2t/τ) .

This represents a moving-averaged power, averaged over one period of the pulsating power. These average results are consistent with Equation (c) above, where τenergy = τ/2.

If we had a resonator in which the power loss was proportional to the potential energy, instead of the kinetic energy, we would see a similar pulsating nature, except that the pulses would be shifted in time, to occur at the peaks of the potential energy instead of the kinetic energy. It is more common for losses to be associated with kinetic energy, however some resonators do have losses proportional to potential energy or some mix of the two (or even to some other factor such as due to sliding friction).

Power loss in the resistor of an LRC circuit resonator.

The power loss in an LRC circuit is entirely in the resistor. That loss is given by Presistor = I2R . Next we calculate this to check that it indeed equals the result we obtained above, i.e. Equation (1c).

| Table 2. Derivation of power loss in a shock excited LRC resonator. | |

|---|---|

(2a)

(2a)

| We repeat an earlier equation for the current in a shock excited LRC circuit resonator as a starting point. |

(2b)

(2b)

| This is a standard equation for the power dissipated by a resistor. We substitute the current from Equation (2a). |

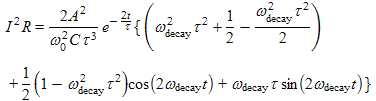

(2c)

(2c)

| We have used sin2θ = 1 − cos2θ and also 2sinθcosθ = sin(2θ) . |

(2d)

(2d)

| Here we used cos2θ = ½+½ cos2θ . |

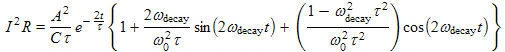

(2e)

(2e)

| This is our final result. We used the relation ωdecay2 = ω02 − 1/τ2 to reduce the constant term inside the braces of Equation (2d) to ½. We see that Equation (2e) is indeed equal to Equation (1c), showing that −dU/dt = Presistor . |

Comparing the results in Equations (1c) and (2e) we see that −dU/dt = Ploss at least in the case of the LRC circuit resonator. It also points out that there are two ways to calculate the power loss. It is often true with physical parameters that there are several ways to calculate a particular quantity, which is good because often one method is easier to use or easier to understand.

P. Ceperley Feb. 2010| All postings by author | previous: 2.5 Energy in a resonator | up: Simple resonators - Contents | next: 2.7 Energy and power by complex methods |