| all topics by author | introduction to relativity | contents-mathematics of relativity | contents-transforming electromagnetic fields | previous: transforming electromagnetic fields | next: four vectors |

13. Transformation of charge and current densities

- The charge on an object will be the same in all reference frames, e.g. the charge of an electron will be the same independent of how fast it is moving.

- Space is subject to Lorentz contractions due to speed.

- The velocity transforms derived above from Lorentz transforms are valid.

- Transformation equations for charge density ρ and current density J.

The object of this chapter is to derive transformations for charge density and current density that allow us to calculate these in one reference frame using values of these in another reference frame. We will assume that we have moving charges from the points of view of both reference frames. It is convenient to use a third reference frame, one in which the charges are stationary. Thus we have three reference frames to keep track of in this chapter. These are summarized in Figure 13.2 below.

The charge on an object is usually assumed to be independent of velocity. This means the charge of an electron will be the same no matter how fast it is moving. Certainly this is consistent with Einstein's idea that physics should look the same in all reference frames. That is, the charge of one electron will be the same and there will be the same number of electrons making up a charge.

Charge density is another matter. Because for charge density, the charge in a tiny volume is divided by the volume and volume is subject to Lorentz contraction; charge density undergoes a transformation when changing reference frames. We might think that is all there is to it, but it turns out that the transformation also involves current density.

To understand this, let's consider a general case involving both charge density and current density, that is we have charges moving at velocity u in the unprimed reference frame. Note that the velocity u has components in all three directions. We call this reference frame, "frame 1" shown in Fig. 13.2b.

For this derivation, we will assume all charges have the same velocity. It would be easy to generalize for the case where charges have various velocities by splitting the charges up into species, each with their own velocity, transforming each separately and then recombining them. Because the transform we will derive next is linear and very simple, it is easy to see that the result will be the same as in the single velocity case.

To start, we need to go back to the reference frame where the charges are stationary. This is possible because we are treating the case where all charges have the same velocity. We call this frame 0 shown in Fig. 13.2a. Another accepted title for this frame is the "proper frame". The charge density in frame 0 is labeled ρ0 . In the following box, we derive the transform between this frame and frame 1.

| Box 13.2. Charge as viewed from the three reference frames and the related γ's | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Fig. 13.2a. View of charge density from the point of view of frame 0, the frame in which the charge is stationary. | Fig. 13.2b. View of moving charge density from the point of view of frame 1. | Fig. 13.2c. View of moving charge density from the point of view of frame 2. |

|

γ concerned with the relative velocity between frames 0 and 1. |

γ concerned with the relative velocity between frames 0 and 2. |

γ concerned with the relative velocity, V, between frames 1 and 2. | ||

| Box 13.3. Velocity and γ in a frame moving with respect to frame 1 |

|---|

|

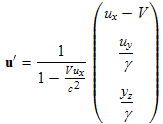

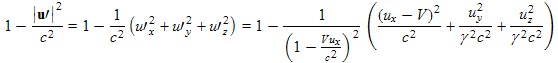

Now we would like to calculate the charge density in a third reference frame, frame 2 shown in Fig. 13.2b. The charges are moving at velocity u' relative to frame 1. Reference frame 2 shown in Fig. 13.2c is moving at velocity V in the x direction relative to frame 1. From equation (9.4) of chapter 9, the velocity of the charges in reference frame 2 in terms of their velocities in frame 1 is given by: where γ (without subscripts) is associated with the relative velocity, V, between reference frames 1 and 2, is shown at the bottom of box 12.2: In our derivation we will need to use u' to calculate γ2 as shown in Box 13.2 above. We first calculate the hardest part of γ2:

Using (13.6) to calculate γ2 , the relativity factor associated with velocity u', we have: where we have used (13.4) to change from velocity u' of these charges in frame 2 (the primed reference frame) to velocity u of the charges in frame 1. |

| Box 13.4. Calculating the charge density in frame 2 |

|---|

|

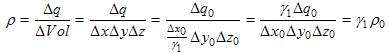

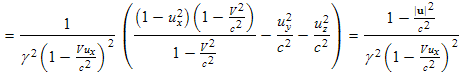

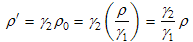

Equation (13.1) above relates the charge density (labelled ρ0 in the frame where it is stationary) to the same charge density (labelled ρ' in this reference frame) as observed in a frame in which this charge is moving. We can write this equation in a more general way as: ρmoving = γρ0 where γ is the relativistic factor written in terms of the relative velocity between these two frames. Equation (13.1) is the application of this equation to the relative motion between frames 0 and 1. We can also applied it to the relative motion between frames 0 and 2, in which case it would be written as:ρ' = γ2ρ0 In the next equation we first use the equation immediately above to relate the charge density as seen in frame 2 to that in frame 0. We then apply (13.1) to relate the charge density in frame 0 to that in frame 1: where γ1 and γ2 are as given in (13.2) and (13.7), respectively. Substituting (13.2) and (13.7) to into (13.8) we get an expression for ρ' (the charge density in reference frame 2) in terms of the parameters of reference frame 1:

where γ (without subscripts) is defined by (13.5) above and relates to the relative velocity, V, between reference frames 1 and 2. |

| Box 13.5. Calculating the current density in frame 2 |

|---|

|

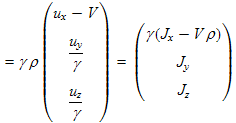

In a similar way using (13.4) and (13.9), we can calculate the current density J':

|

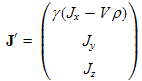

| Box 13.6. Summary - current density/charge density transform |

|---|

|

Summarizing what we have derived above (equations (13.9) and (13.10)), we have: We might have guessed the transform for current density would be that shown in (13.12). That is, the γ is simply due to the length contraction which concentrates the charge when it is moving. Since current is just charge times velocity, this concentration will have the same multiplying effect on current density. The second, or γVρ term is simply the extra current due to the fact that in this reference frame, the charge is moving and becomes a current density in addition to its role as a charge density. The first term in (13.11) is also easy to explain. It is simply the same charge multiplied by the γ factor which is again due to length contraction. Harder to explain on an intuitive basis is the second term in (13.11). That is, "how does a current density become a charge density?" I don't know an easy way to explain it. To get the formula for it you need to go through the above math. |

| all topics by author | introduction to relativity | contents-mathematics of relativity | contents-transforming electromagnetic fields | previous: transforming electromagnetic fields | next: four vectors |

, (13.1)

, (13.1)

. (13.6)

. (13.6)

, (13.9)

, (13.9) .

.